| The Iron Giant | |

|---|---|

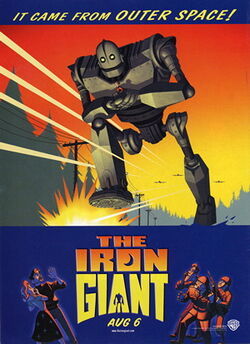

Theatrical release poster | |

| Film information | |

|

Directed by |

Brad Bird |

|

Produced by |

Pete Townshend |

|

Music by |

Michael Kamen |

|

Cinematography |

Steven Wilzbach |

|

Studio |

Warner Bros. Feature Animation |

|

Distributed by |

|

|

Language |

English |

|

Budget |

|

|

Gross Revenue |

$31,333,917[1] |

The Iron Giant is a 1999 animated science fiction action drama film utilizing both traditional animation and computer animation, produced by Warner Bros. Animation, and based on the 1968 novel The Iron Man by Ted Hughes. The film is directed by Brad Bird, and features the voices of Jennifer Aniston, Harry Connick, Jr., Vin Diesel, Eli Marienthal, Christopher McDonald, and John Mahoney.

The film is about a lonely boy named Hogarth raised by his mother (widowed to an Air Force pilot), who discovers an iron giant who fell from space. With the help of a beatnik named Dean, they have to stop the U.S. military and a federal agent from finding and destroying the Giant. The Iron Giant takes place in October 1957 in the American state of Maine during the height of the Cold War.

The film's development phase began around 1994, though the project finally started taking root once Bird signed on as director, and his hiring of Tim McCanlies to write the screenplay in 1996. The script was given approval by Ted Hughes, author of the original novel, and production struggled through difficulties (Bird even enlisted the aid of a group of students from CalArts). The Iron Giant was released by Warner Bros. in the summer of 1999 and received high critical praise (scoring a 97% approval rating from Rotten Tomatoes). It was nominated for several awards that most notably included the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and the Nebula Award from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America.

Plot

In 1957, a large alien robot crashes from orbit near the coast of Rockwell, Maine with no memory. Shortly after, the Iron Giant wanders off into the mainland. Nine-year-old Hogarth Hughes follows a trail of the forest's destruction and frees the robot, who is stuck in the power cables of an electrical substation. After being rescued by and befriended by Hogarth, the Giant follows him back to his house, where he lives with his mother Annie. Upon their return, the robot attempts to eat the iron off the nearby railroad tracks. Alarmed at the sound of an incoming train, Hogarth tells the giant to repair the tracks. The robot attempts this, but takes too long, causing the train to collide with his head. Hogarth hides the damaged robot in their barn where he discovers the robot is self repairing.

Later that night, Hogarth returns to the barn with a stack of comic books to read to the Giant. The robot is impressed with Superman, but distressed when he discovers a comic about an evil robot; Hogarth tells the robot that it can be who he chooses to be. Investigating the destroyed substation, U.S. government agent Kent Mansley discovers evidence of the robot and decides to continue his inquiries in nearby Rockwell. Finding a BB gun Hogarth left near the substation the night he found the Giant, Mansley takes up a room for rent at Hogarth's home and trails the boy to learn more. Hogarth says to the robot to dive in the lake which it does, creating a tsunami that sweeps Dean onto the road. Mansley is paranoid about an alien invasion and alerts the U.S. Army to the possible presence of the robot. Worried that they will get caught, Hogarth evades Mansley and takes the robot to beatnik artist Dean McCoppin who passes off the robot as one of his works of art when Mansley and Lieutenant General Rogard investigate. Hogarth inadvertently activates a self-defense mechanism (SDM) in the giant with a toy gun, but Dean saves Hogarth. Commanding the robot to leave, they soon realize that the robot cannot control the SDM, and they chase after it before reaching town.

In Rockwell, the robot saves two boys, but Mansley, having seen it, orders an attack to stop it. The robot flees with Hogarth until he is shot down by a missile, and after crash landing, the robot believes Hogarth to be dead, causing the enraged robot to activate its weapons and attack the Army, who are no match for the advanced firepower. Mansley lies to Rogard that the robot killed Hogarth, before telling him to lure the robot out to sea so they can destroy it with a nuclear ballistic missile from the USS Nautilus. Hogarth (alive the whole time) wakes up and calms the robot down, causing it to deactivate its weapons. Dean tells Rogard and his men to stand down. Rogard, realizing that Mansley lied to him, is about to tell the Nautilus to stand down, but Mansley snatches the walkie-talkie and calls the Nautilus to launch the missile anyway. Realizing the deadly mistake, Rogard argues with Mansley and informs him that the robot, along with everybody in Rockwell will be destroyed when the missile falls. Mansley refuses to take note of the town's fate and tries to escape Rockwell in order to save himself, but the robot stops Mansley, who is then arrested by the Army. When Hogarth tells the robot about Rockwell's fate, the robot flies off to intercept the missile, as a hero, not a weapon. The robot and missile collide, causing a massive explosion high up in the atmosphere. The people of the town recognize the giant as a hero, but everyone, especially Hogarth, is deeply saddened by the robot's sacrifice.

Some time later, Annie and Dean have a romantic relationship and Dean creates a statue honoring the robot. Hogarth receives a package from Rogard, containing the only piece of the robot they found, a small jaw bolt. That night, Hogarth awakens to a familiar beeping coming from the bolt, which is trying to get out his window. He knows the robot is repairing itself somewhere and he opens it to let the bolt out. On the Langjökull glacier in Iceland various parts of the robot travel across there where his head rests, eyes glowing, as the robot wakes up and smiles.

Cast

Christopher McDonald, Brad Bird and Eli Marienthal in March 2012 at the Iron Giant screening at the LA Animation Festival

- Eli Marienthal as Hogarth Hughes, an energetic, young, curious boy with an active imagination.

- Jennifer Aniston as Annie Hughes, a widow and Hogarth's single mother.

- Harry Connick, Jr. as Dean McCoppin, a beatnik artist and junkyard owner who "sees art where others see junk".

- Vin Diesel as The Iron Giant, fifty-foot, metal-eating robot. The Giant reacts defensively if it recognizes anything as a weapon, immediately attempting to destroy it, but can stop himself. The specific creator of the giant is never revealed. In a deleted scene, he has a brief vision of robots similar to him destroying a different planet. Peter Cullen was considered to do the voice.

- Christopher McDonald as Kent Mansley, an arrogant, ambitious and paranoid N.S.A. agent sent to investigate the Iron Giant.

- John Mahoney as General Rogard, the military leader in Washington, D.C. who strongly dislikes Mansley.

- M. Emmet Walsh as Earl Stutz, a sailor and the first man to see the robot.

- James Gammon as Marv Loach, a foreman who follows the robot's trail after it destroys the power station.

- Cloris Leachman as Mrs. Tensedge, Hogarth's no-nonsense schoolteacher.

Production

Development

In 1986, rock musician Pete Townshend became interested in writing "a modern song-cycle in the manner of Tommy",[3] and chose Ted Hughes' The Iron Man as his subject. Three years later, The Iron Man: A Musical album was released. The same year Pete Townshend produced a short film set to the album single "A Friend is a Friend" featuring The Iron Man in a mix of stop frame animation and live action directed by Matt Forrest. In 1993, a stage version was mounted at London’s Old Vic. Des McAnuff, who had adapted Tommy with Townshend for the stage, believed that The Iron Man could translate to the screen, and the project was ultimately acquired by Warner Bros.[3]

In late 1996, while developing the project on its way through, the studio saw the film as a perfect vehicle for Brad Bird, who at the time was working for Turner Feature Animation.[3] Turner Entertainment had recently merged with Warner Bros. parent company Time Warner, and Bird was allowed to transfer to the Warner Bros. Animation studio to direct The Iron Giant.[3] After reading the original Iron Man book by Hughes, Bird was impressed with the mythology of the story and in addition, was given an unusual amount of creative control by Warner Bros.[3] This creative control involved introducing two new characters not present in the original book: Dean and Kent. Bird's pitch to Warner Bros. was based around the idea "What if a gun had a soul?"[4] Bird decided to have the story set to take place in the 1950s as he felt the time period "presented a wholesome surface, yet beneath the wholesome surface was this incredible paranoia. We were all going to die in a freak-out."

The financial failure of Warner Bros.' previous animated effort, Quest for Camelot, whose cost overruns and production nightmares made the company reconsider their commitment to feature animation, helped shape The Iron Giant's production considerably. In a 2003 interview, writer Tim McCanlies recalled "Quest for Camelot did so badly that everybody backed away from animation and fired people. Suddenly we had no executive anymore on Iron Giant, which was great because Brad got to make his movie. Because nobody was watching." Bird, who regarded Camelot as "trying to emulate the Disney style," attributed the creative freedom on The Iron Giant to the bad experience of Quest for Camelot, stating: "I caught them at a very strange time, and in many ways a fortuitous time." By the time The Iron Giant entered production, Warner Bros. informed the staff that there would be a smaller budget as well as time-frame to get the film completed. However, although the production was watched closely, Bird commented "They did leave us alone if we kept it in control and showed them we were producing the film responsibly and getting it done on time and doing stuff that was good." Bird regarded the tradeoff as having "one-third of the money of a Disney or DreamWorks film, and half of the production schedule," but the payoff as having more creative freedom, describing the film as "fully-made by the animation team; I don't think any other studio can say that to the level that we can."

Writing

Tim McCanlies was hired to write the script, though Bird was somewhat displeased with having another writer on board, as he himself wanted to write the screenplay.[5] He later changed his mind after reading McCanlies' unproduced screenplay for Secondhand Lions.[3] In Bird's original story treatment, America and the USSR were at war at the end, with the Giant dying. McCanlies decided to have a brief scene displaying his survival, stating, "You can't kill E.T. and then not bring him back." McCanlies finished the script within two months, and was surprised once Bird convinced the studio not to use Townshend's songs. Townshend did not care either way, saying "Well, whatever, I got paid."[5] McCanlies was given a three month schedule to complete a script, and it was by way of the film's tight schedule that Warner Bros. "didn't have time to mess with us" as McCanlies said.[6] Hughes himself was sent a copy of McCanlies' script and sent a letter back, saying how pleased he was with the version. In the letter, Hughes stated, "I want to tell you how much I like what Brad Bird has done. He’s made something all of a piece, with terrific sinister gathering momentum and the ending came to me as a glorious piece of amazement. He’s made a terrific dramatic situation out of the way he’s developed The Iron Giant. I can’t stop thinking about it."[3]

Animation

Bird opted to produce The Iron Giant entirely in the widescreen CinemaScope format, but was warned against doing so by his advisors. Bird felt it was appropriate to use the format, as many films from the late 1950s were produced in such widescreen formats, and was eventually allowed to produce the feature in the wide 2.39:1 CinemaScope aspect ratio [7] It was decided to animate the Giant using computer-generated imagery as the various animators working on the film found it hard "drawing a metal object in a fluid-like manner."[3] A new computer program was created for this task, while the art of Norman Rockwell, Edward Hopper and N.C. Wyeth inspired the design. Bird brought in students from CalArts to assist in minor animation work due to the film's busy schedule. The Giant's voice was originally to be electronically modulated but the filmmakers decided they "needed a deep, resonant and expressive voice to start with", and were about to hire Peter Cullen, due to his recent history with voice acting robot characters, but, due to Cullen's unavailability at the time, Vin Diesel was hired instead.[3] Cullen, however, did some voice-over work for the film's theatrical trailer. Teddy Newton, a storyboard artist, played an important role in shaping the film's story. Newton's first assignment on staff involved being asked by Bird to create a film within a film to reflect the "hygiene-type movies that everyone saw when the bomb scare was happening."

Newton came to the conclusion that a musical number would be the catchiest alternative, and the "Duck and Cover sequence" came to become one of the crew members' favorites of the film.[8] Nicknamed "The X-Factor" by story department head Jeffery Lynch, the producers gave him artistic freedom on various pieces of the film's script.[9]

Music

The score for the film was composed and conducted by Michael Kamen. Bird's original temp score, "a collection of Bernard Hermann cues from 50's and 60's sci-fi films," initially scared Kamen.[10] Believing the sound of the orchestra is important to the feeling of the film, Kamen "decided to comb eastern Europe for an "old-fashioned" sounding orchestra and went to Prague to hear Vladimir Ashkenazy conduct the Czech Philharmonic in Strauss's An Alpine Symphony." Eventually, the Czech Philharmonic was the orchestra used for the film's score, with Bird describing the symphony orchestra as "an amazing collection of musicians."[11] The score for The Iron Giant was recorded in a rather unconventional manner, compared to most films: recorded over one week at the Rudolfinum in Prague, the music was recorded without conventional uses of syncing the music, in a method Kamen described in a 1999 interview as "[being able to] play the music as if it were a piece of classical repertoire."[10] Kamen's score for the feature was nominated and won an Annie Award for Music in an Animated Feature Production on November 6, 1999.[12]

Themes

The film is set in 1957 during a period of the Cold War characterized by escalation in tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1957, Sputnik was launched, raising the possibility of nuclear attack from space. Anti-communism and the potential threat of nuclear destruction cultivated an atmosphere of fear and paranoia which also led to a proliferation of films about alien invasion. In one scene, Hogarth's class is seen watching an animated film named Atomic Holocaust, based on Duck and Cover, an actual film that offered advice on how to survive if the USSR bombed the USA. The film also has an anti-gun message in it. When the Iron Giant sees a deer get killed by hunters, the Iron Giant notices two rifles discarded by the deer's body. The Iron Giant's eyes turn red showing hostility to any gun. It is repeated throughout the film, "Guns kill." and "You're not a gun." Despite the anti-war and anti-gun themes, the film avoids demonizing the military, and presents General Rogard as an essentially rational and sympathetic figure, in contrast to the power-hungry civilian Mansley. Hogarth's message to the giant, "You are who you choose to be", played a pivotal role in the film. Writer Tim McCanlies commented that "At a certain point, there are deciding moments when we pick who we want to be. And that plays out for the rest of your life." McCanlies said that movies can provide viewers with a sense of right and wrong, and expressed a wish that the movie would "make us feel like we're all part of humanity [which] is something we need to feel." [6]

Reception

Box office

| "We had toy people and all of that kind of material ready to go, but all of that takes a year! Burger King and the like wanted to be involved. In April we showed them the movie, and we were on time. They said, "You'll never be ready on time." No, we were ready on time. We showed it to them in April and they said, "We'll put it out in a couple of months." That's a major studio, they have 30 movies a year, and they just throw them off the dock and see if they either sink or swim, because they've got the next one in right behind it. After they saw the reviews they [Warner Bros.] were a little shamefaced." |

| — Writer Tim McCanlies on Warner Bros.' marketing approach[5] |

The Iron Giant opened on August 6, 1999 in the United States in 2,179 theaters, accumulating $5,732,614 over its opening weekend. The film went on to gross $23,159,305 domestically and $8,174,612 internationally to make a total of $31,333,917 worldwide making it a failure.[1][2] In an interview with Brad Bird, IGN stated that it was "a mis-marketing campaign of epic proportions at the hands of Warner Bros., they simply didn't realize what they had on their hands."[13] Tim McCanlies said, "I wish that Warner had known how to release it."[5]

Lorenzo di Bonaventura, president of Warner Bros. at the time, explained, "People always say to me, 'Why don't you make smarter family movies?' The lesson is, Every time you do, you get slaughtered."[14] Stung by criticism that it mounted an ineffective marketing campaign for its theatrical release, Warner Bros. revamped its ad strategy for the video release of the film, including tie-ins with Honey Nut Cheerios, AOL and General Motors and secured the backing of three U.S. congressmen (Ed Markey, Mark Foley and Howard Berman).[15]

Critical response

The Iron Giant earned very positive reviews from critics; based on 111 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, The Iron Giant received an overall 97% "Certified Fresh" approval rating.[16] With the 31 critics on Rotten Tomatoes' "Cream of the Crop", which consists of popular and notable critics from the top newspapers, websites, television and radio programs,[17] still averaging a 97% "Certified Fresh" approval rating.[18] By comparison, Metacritic calculated an average score of 85 (out of 100) from the 27 reviews it collected, which indicates "Universal Acclaim".[19] The film has since then gathered a cult following.[13] The cable television network Cartoon Network showed the film annually on Thanksgiving for 24 hours straight in the early 2000s.[20]

Roger Ebert very much liked the Cold War setting, feeling "that's the decade when science fiction seemed most preoccupied with nuclear holocaust and invaders from outer space." In addition he was impressed with parallels seen in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and wrote, "[The Iron Giant] is not just a cute romp but an involving story that has something to say."[21] In response to the E.T. parallels, Bird said, "E.T. doesn't go kicking ass. He doesn't make the Army pay. Certainly you risk having your hip credentials taken away if you want to evoke anything sad or genuinely heartfelt."[7] IGN extolled the film in a 2004 review as "the best non-Disney animated film".[20]

Peter Stack of the San Francisco Chronicle agreed that the storytelling was far superior to other animated films, and cited the characters as plausible and noted the richness of moral themes.[22] Jeff Millar of the Houston Chronicle agreed with the basic techniques as well, and concluded the voice cast being excelled with a great script by Tim McCanlies.[23]

Accolades

The Hugo Awards nominated The Iron Giant for Best Dramatic Presentation,[24] while the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America honored Brad Bird and Tim McCanlies with the Nebula Award nomination.[25] The British Academy of Film and Television Arts gave the film a Children's Award as Best Feature Film.[26] In addition The Iron Giant won nine Annie Awards and was nominated for another six categories,[27] with another nomination for Best Home Video Release at The Saturn Awards.[28] IGN ranked The Iron Giant as the fifth favorite animated film of all time in a list published in 2010.[29]

The American Film Institute nominated The Iron Giant for its Top 10 Animated Films list.[30]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednumbers - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmojo - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Template:Cite news

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite video

- ↑ Template:Cite video

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite episode

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news Template:Dead link

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ AFI's 10 Top 10 Ballot

- Further reading

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

External links

Template:Portal Template:Wikiquote

- Template:Imdb title

- Template:Bcdb title

- Template:Allrovi movie

- Template:Mojo title

- Template:Rotten-tomatoes

- Template:Metacritic film

- The Iron Giant at Open Directory Project

Template:Brad Bird Template:Annie Award for Best Animated Feature Template:Good article