Template:Infobox television show Dexter's Laboratory (commonly abbreviated as Dexter's Lab) is an American comic science fiction animated television series created by Genndy Tartakovsky for Cartoon Network, and the first of the network's Cartoon Cartoons. The series follows Dexter, a boy-genius and inventor with a secret laboratory, who constantly battles his sister Dee Dee in an attempt to keep her out of the lab. He also engages in a bitter rivalry with his neighbor and fellow-genius Mandark. The first two seasons contained additional segments: Dial M for Monkey, which focuses on Dexter's pet lab-monkey/superhero, and The Justice Friends, about a trio of superheroes who share an apartment.

Tartakovsky pitched the series to Hanna-Barbera's animated shorts showcase What a Cartoon!, basing it on student films he produced while attending the California Institute of the Arts. A pilot aired on Cartoon Network in February 1995 and another pilot also aired on the network in March 1996; viewer approval ratings convinced Cartoon Network to order a half-hour series, which premiered on April 28, 1996. On December 10, 1999, a television movie titled Dexter's Laboratory: Ego Trip aired as the intended series finale, and Tartakovsky left to begin work on his new series, Samurai Jack. However, in 2001, the network revived the series under a different production team at Cartoon Network Studios. It ended on November 20, 2003, with a total of four seasons and 78 episodes.

Dexter's Laboratory received high ratings and became one of Cartoon Network's most popular and successful original series. During its run, the series won three Annie Awards, with nominations for four Primetime Emmy Awards, four Golden Reel Awards, and nine additional Annie Awards. The series is notable for helping launch the careers of several cartoonists, such as Craig McCracken, Seth MacFarlane, Butch Hartman, and Rob Renzetti. Spin-off media include comic books, DVD and VHS releases, music albums, collectible toys, and video games.

Premise

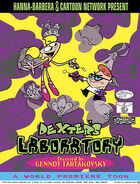

Poster for the series' pilot, where Dexter (right) and his sister Dee Dee (left) fight over a device that transforms people into animals

The series revolves around Dexter (voiced by Christine Cavanaugh in seasons 1–3; Candi Milo in seasons 3–4), a bespectacled boy-genius who possesses a secret laboratory hidden behind a bookcase in his bedroom. The laboratory is filled with Dexter's inventions and can be accessed by speaking various passwords or by activating hidden switches on Dexter's bookshelf (e.g. pulling out a specific book). Though highly intelligent, Dexter often fails at what he has set out to do when he becomes overexcited and makes careless choices. Although he comes from a typical all-American family, Dexter speaks with a thick accent of indeterminate origin. Cavanaugh described it as "an affectation, some kind of accent, we're not quite sure. A small Peter Lorre, but not. Perhaps he's Latino, perhaps he's French. He's a scientist; he knows he needs some kind of accent."[1] Genndy Tartakovsky explained, "He considers himself a very serious scientist, and all well-known scientists have accents."[2]

Dexter manages to keep the lab a secret from his clueless, cheerful Mom (Kath Soucie) and Dad (Jeff Bennett), who never take notice of it. However, he is frequently in conflict with his hyperactive older sister, Dee Dee (Allison Moore in seasons 1 and 3; Kathryn Cressida in seasons 2 and 4). In spite of Dexter's advanced technology, Dee Dee eludes all manner of security, and once inside her brother's laboratory, she delights in playing haphazardly, often wreaking havoc with his inventions. Though seemingly dim-witted, Dee Dee often outsmarts her brother and even gives him helpful advice. For his part, Dexter, though annoyed by his intrusive sibling, feels a reluctant affection for her and will come to her defense if she is imperiled.

Dexter's nemesis is a rival boy-genius from his school named Susan "Mandark" Astronomonov[3][4] (Eddie Deezen). Just like Dexter, Mandark also has his own laboratory, but his schemes are generally evil and designed to gain power while downplaying or destroying Dexter's accomplishments. In the revival seasons, Mandark becomes significantly more evil, becoming Dexter's enemy rather than his rival and his laboratory changing from brightly-lit with rounded features to gothic-looking, industrial, and angular. Because Dexter's inventions are often better than his, Mandark tries to make up for this by stealing Dexter's plans. Mandark's weakness is his love for Dee Dee, though she ignores him and never returns his affections.

Recurring segments

Almost every episode of Dexter's Laboratory is divided into three different stories/segments, each one being approximately 8 minutes in length. Occasionally, the middle segment centered on characters from the Dexter's Laboratory universe other than Dexter and his family. Two of these segments were shown primarily during the first season: Dial M for Monkey and The Justice Friends.[5] Dial M for Monkey was the middle segment for the first six episodes of season one, and The Justice Friends took its place for the rest of the season.

The Dial M for Monkey shorts feature Dexter's pet laboratory monkey, Monkey (Frank Welker), whom Dexter believes is an ordinary monkey and nothing more. However, Monkey secretly has superpowers and fights evil as the superhero Monkey. Monkey is joined by his partner Agent Honeydew (Kath Soucie), the Commander General (Robert Ridgely; Earl Boen), and a team of assembled superheroes. Dial M for Monkey was created by Genndy Tartakovsky, Craig McCracken, and Paul Rudish.[6]

The Justice Friends consists of Major Glory (Rob Paulsen), Valhallen (Tom Kenny), and the Infraggable Krunk (Frank Welker), three superheroes who are all roommates living in an apartment complex called Muscular Arms. Most of the trio's adventures deal less with their lives as superheroes and more with their inability to get along as roommates; it is presented as a sitcom, including a laugh track. Genndy Tartakovsky's inspiration for The Justice Friends came from reading Marvel Comics when he was learning how to speak English.[7] Tartakovsky stated in an interview with IGN that he was somewhat disappointed with how The Justice Friends turned out, saying, "it could have been funnier and the characters could have been fleshed out more."[8]

Between the three main segments in seasons one and two are brief mini-segments, many of which feature only Dexter and Dee Dee. Other characters from the series may star in them also, such as "The Puppet Pals", two live-action puppets named Puppet Pal Mitch (Rob Paulsen) and Puppet Pal Clem (Tom Kenny).

Production

Development

Dexter's Laboratory creator Genndy Tartakovsky

Dexter's Laboratory was inspired by one of Genndy Tartakovsky's drawings of a ballerina.[9][10] After drawing Dee Dee's tall, thin shape, he decided to pair her with a short and blocky opposite, Dexter, inspired by Tartakovsky's older brother Alex.[11] After enrolling at the California Institute of the Arts in 1990 to study animation, Tartakovsky wrote, directed, animated, and produced two short films that would become the basis for the series.[12]

Dexter's Laboratory was then made into a seven-minute pilot as a part of Cartoon Network's What a Cartoon! project, promoted as World Premiere Toons, which debuted on February 26, 1995.[13] Viewers worldwide voted through phone lines, the Internet, focus groups, and consumer promotions for their favorite short cartoons; the first of 16 animated shorts to earn that vote of approval was Dexter's Laboratory.[6] Mike Lazzo, then-head of programming for the network, said that it was his favorite of the 48 shorts, commenting "We all loved the humor in brother-versus-sister relationship".[14] In August 1995, Turner ordered six half-hours of the series, which would include two cartoons around one spin-off segment titled Dial M for Monkey.[6]

Original run

Dexter's Laboratory premiered as a half-hour series on TNT on April 27, 1996, and on April 28 on Cartoon Network and TBS Superstation.[15] The series, along with Cow and Chicken, Johnny Bravo, The Powerpuff Girls, and Courage the Cowardly Dog, became responsible for pushing Cartoon Network in a new direction focusing on original programming and "character-driven" cartoons.[16] A second season was ordered, and premiered on Cartoon Network on July 16, 1997.[5]

Dexter's Laboratory ended its initial run in 1998 after two seasons, with the second season lasting 39 episodes; a notable record for a single TV production season on Cartoon Network.[17] The initial series finale was "Last But Not Beast", which differed from the format of the other episodes in that it was not a collection of cartoon shorts, but was a single 25-minute episode.

In 1999, Tartakovsky returned to direct Dexter's Laboratory: Ego Trip, an hour-long television movie.[18] This was the last Dexter's Laboratory production that Tartakovsky was involved with and was originally intended to be the conclusion to the series. The special was hand-animated, though the character and setting designs were subtly revised. The plot follows Dexter on a quest through time as he finds out his future triumphs.[18]

Revival

After the series ended, Tartakovsky began work on his new projects, Samurai Jack and Star Wars: Clone Wars.[7][19] MacFarlane and Hartman had left Time Warner altogether at this point, focusing on Family Guy and The Fairly OddParents, respectively.[20][21]

On February 21, 2001, Cartoon Network announced Dexter's Laboratory had been revived for a 13-episode third season.[22] The series was given a new production team at Cartoon Network Studios, with Chris Savino taking over as the creative director in Tartakovsky's absence. Later in season four, Savino was also promoted to producer giving him further control over the show, such as the budget.[23] The revival episodes featured revised visual designs and sound effects, recast voice actors, and continuity shakeups.

Direction and writing

Directors and writers on the series included Tartakovsky,[24] McCracken,[24] Seth MacFarlane,[20] Butch Hartman,[21] Rob Renzetti,[25] Paul Rudish,[24] John McIntyre,[26] and Chris Savino.[27]

Casting

Christine Cavanaugh voiced Dexter for the first two seasons and early episodes of the third, but retired from voice acting in 2001 for personal reasons. She was replaced by Candi Milo.[17]

Allison Moore, a college friend of Tartakovsky, was cast as Dee Dee. She left the show after the first season because she was no longer interested in voice acting.Template:Citation needed The role was subsequently recast with Kathryn Cressida.[28] In season three, Moore briefly returned as Dee Dee's voice before Cressida once again assumed the role for season four.

Animation

The series was animated in a stylized way, which Tartakovsky says was influenced by the Merrie Melodies cartoon The Dover Boys at Pimento University.[29] Dexter's Laboratory, however, was staged in a cinematic way, rather than flat and close to the screen, to leave space and depth for the action and gags. Tartakovsky was also influenced by other Warner Bros. cartoons, Hanna-Barbera, Japanese mecha anime, and the UPA shorts.

Tartakovsky has said the character Dexter was designed "as an icon"—his body is short and squat and his design is simple, with a black outline and relatively little detail. Since he knew that he was designing the show for television, he purposely limited the design to a certain degree, designing the nose and mouth, for instance, in a Hanna-Barbera style to animate easily.[30]

Episodes

- Main article: Dexter's Laboratory episode list

Dexter's Laboratory broadcast 78 half-hour episodes over 4 seasons during its 7-year run. Two pilot shorts were produced for What a Cartoon! that aired from 1995 to 1996, and were reconnected into the series' first season in later airings. Fifty-two episodes were produced over the original run from 1996 to 1998, which was followed by the TV movie Ego Trip in 1999.

An additional 26 episodes were produced and broadcast from 2001 to 2003. The short "Chicken Scratch" debuted theatrically with The Powerpuff Girls Movie in 2002, and was later broadcast as a segment in the series' fourth and final season.[31]

Broadcast

On December 31, 2000, Cartoon Network aired its "New Year's Bash" marathon featuring Dexter's Laboratory among other programs.[32] On November 16, 2001, the network broadcast the 12-hour "Dexter Goes Global" marathon in 96 countries and 12 languages.[33] The marathon featured fan-selected episodes of Dexter's Laboratory and culminated with the premiere of the first two episodes of season 3.[33]

After the series ended, reruns continued to air prominently on Cartoon Network from November 21, 2003, to July 29, 2005.[34] From September 12, 2005, to June 1, 2008, it was reran in segments on The Cartoon Cartoon Show, along with other Cartoon Cartoons from that era. On March 30, 2012, the series returned to the network in reruns on the revived block, Cartoon Planet.[35]

On January 16, 2006, the series began airing in reruns on Cartoon Network's sister channel Boomerang; the occasion was marked by a 12-hour Martin Luther King, Jr. Day marathon.[36] Reruns of the series was removed from Boomerang on January 4, 2015 along with Johnny Bravo Teen Titans and Ed, Edd n Eddy Before the rebrand.

The Canadian version of Cartoon Network airs reruns as well, with the series being featured on the channel's launch on July 4, 2012.[37] The launch was commemorated by parent network Teletoon, which aired Cartoon Network-related programming blocks and promotions in the weeks leading up to the event, including episodes of Dexter's Laboratory.[38]

Controversial episodes

The segment "Dial M for Monkey: Barbequor" (season one, 1996) was removed from rotation after a few years of being broadcast in the United States. The short features a character named the Silver Spooner (a spoof of the Silver Surfer), which was perceived by Cartoon Network as a stereotype of gay men and because Krunk becomes drunk, has a hangover and vomits.[39][40] In later broadcasts and on the Season One DVD (Region 1), the banned segment has been replaced with "Dexter's Lab: A Story", an episode from season two.[41]

During the initial run of Dexter's Lab, a segment titled "Rude Removal" (season two, 1997) was produced. The short involves Dexter creating a "rude removal system" to diminish Dee Dee's rudeness; however, it instead creates highly rude clones of both siblings. The episode was only shown during certain animation festivals and was never aired on Cartoon Network or any television channel due to the characters swearing, even though the swear words were censored.[42] Tartakovsky commented that "standards didn't like it."[43] Linda Simensky, then-vice president of original programming for Cartoon Network, said "I still think it's very funny. It probably would air better late at night."[42] Fred Seibert, president of Hanna-Barbera Cartoons from 1992 to 1996, has attested to the existence of the short.[43]

In October 2012, Genndy Tartakovsky was asked about the episode during an AMA on Reddit, and he replied "Next time I do a public appearance I'll bring it with me!".[44] Adult Swim later asked fans on Twitter if there was still any interest in the episode, and the response was "overwhelming".[45][46] The episode was finally uploaded on AdultSwim.com via YouTube on January 22, 2013.[47]

Reception

Ratings

Since its debut, Dexter's Laboratory has been one of Cartoon Network's most successful original series, being the network's highest-rated original series in both 1996 and 1997.[48] Internationally, the series garnered a special mention for best script at the 1997 Cartoons on the Bay animation festival in Italy.[49] In 1998 and 1999, a Dexter balloon was featured in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade alongside many other iconic characters, including the titular piglet from the movie Babe whom Christine Cavanaugh also voiced.[50][51] The show was also part of the reason for Cartoon Network's 20% ratings surge over the summer of 1999.[52] The series' July 7, 2000, telecast was the network's highest-rated original telecast of all time among households (3.1), kids 2–11 (7.8), and kids 6–11 (8.4), with a delivery of almost 2 million homes.[53] On July 31, 2001, it scored the highest household rating (2.9) and delivery (2,166,000 homes) of any Cartoon Network telecast for that year.[54] Dexter's Laboratory was also one of the network's highest-rated original series of 2002.[55]

Critical reception

One of Cartoon Network president Betty Cohen's favorite animated shows was Dexter's Laboratory.[52] Rapper Coolio has also said that he is a fan of the show and was happy to do a song for the show's soundtrack at Cartoon Network's request, stating, "I watch a lot of cartoons because I have kids. I actually watch more cartoons than movies."[56]

In a 2012 top 10 list by Entertainment Weekly, Dexter's Laboratory was ranked as the fourth best Cartoon Network show.[57] In 2009 Dexter's Laboratory was named the 72nd best animated series by IGN, with editors remarking, "While aimed at and immediately accessible to children, Dexter's Laboratory was part of a new generation of animated series that played on two levels, simultaneously fun for both kids and adults."[58]

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Annie Awards | Best Animated Short Subject[59] | Hanna-Barbera Template:Small |

Template:Won |

| Best Individual Achievement: Storyboarding in the Field of Animation[59] | Genndy Tartakovsky | Template:Nom | ||

| Primetime Emmys | Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming One Hour or Less)[60] | Buzz Potamkin, Genndy Tartakovsky, and Larry Huber Template:Small |

Template:Nom | |

| 1996 | Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming One Hour or Less)[61] | Larry Huber, Genndy Tartakovsky, Craig McCracken, and Paul Rudish Template:Small |

Template:Nom | |

| 1997 | Annie Awards | Best Individual Achievement: Writing in a TV Production[62] | Jason Butler Rote and Paul Rudish Template:Small |

Template:Won |

| Best Animated TV Program[62] | Hanna-Barbera | Template:Nom | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Music in a TV Production[62] | Thomas Chase and Steve Rucker | Template:Nom | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Producing in a TV Production[62] | Genndy Tartakovsky Template:Small |

Template:Nom | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Voice Acting by a Female Performer in a TV Production[62] | Christine Cavanaugh Template:Small |

Template:Nom | ||

| Primetime Emmys | Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming One Hour or Less)[61] | Sherry Gunther, Larry Huber, Craig McCracken, Genndy Tartakovsky, and Jason Butler Rote Template:Small |

Template:Nom | |

| 1998 | Annie Awards | Outstanding Achievement in an Animated Primetime or Late Night Television Program[63] | Hanna-Barbera | Template:Nom |

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Voice Acting by a Female Performer in an Animated Television Production[63] | Christine Cavanaugh Template:Small |

Template:Nom | ||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Music in an Animated Television Production[63] | David Smith, Thomas Chase, and Steve Rucker Template:Small |

Template:Nom | ||

| Primetime Emmys | Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming One Hour or Less)[61] | Davis Doi, Genndy Tartakovsky, Jason Butler Rote, and Michael Ryan Template:Small |

Template:Nom | |

| Golden Reel Award | Best Sound Editing in Television Animation — Music | Dexter's Laboratory | Template:Nom | |

| 2000 | Annie Awards | Outstanding Achievement in a Primetime or Late Night Animated Television Program[64] | Hanna-Barbera | Template:Nom |

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Voice Acting by a Female Performer in an Animated Television Production[64] | Christine Cavanaugh Template:Small |

Template:Won | ||

| 2002 | Golden Reel Award | Best Sound Editing in Television — Music, Episodic Animation | Roy Braverman and William Griggs Template:Small |

Template:Nom |

| 2004 | Best Sound Editing in Television Animation — Music | Brian F. Mars and Roy Braverman Template:Small |

Template:Nom |

Merchandise

Comics

Characters from Dexter's Laboratory appeared in a 150,000-print magazine called Cartoon Network, published by Burghley Publishing and released in the United Kingdom on August 27, 1998.[65]

DC Comics printed four comic book volumes featuring Dexter's Laboratory. It first appeared in Cartoon Network Presents, a 24-issue volume showcasing the network's premiere animated programming at the time, which was produced from 1997 to 1999. In 1999, DC gave the show its own 34-issue comic volume, which ran until 2003. DC also ran a Cartoon Cartoons comic book from 2001 to 2004 that frequently contained Dexter's Laboratory stories. This was superseded by Cartoon Network Block Party, which ran from 2004 to 2009.

In February 2013, IDW Publishing announced a partnership with Cartoon Network to produce comics based on its properties. Dexter's Laboratory was one of the titles announced to be published.[66] The first issue was released in April 2014.[67]

Home media releases

Dexter's Laboratory first appeared in home media on three VHS tapes made widely available in the early 2000s. Episodes had not been officially released prior to this, with the exception of a complete series DVD collection given as a contest prize.

Warner Bros. stated in a 2006 interview that they were "...in conversations with Cartoon Network" for DVD collections of various cartoons, among which was Dexter's Laboratory.[68] Madman Entertainment released the complete first season and the first part of the second season in Region 4 in 2008.[69][70] A Region 1 release of the first season was released by Warner Home Video on October 12, 2010.[71] The release was the third in an official release of several Cartoon Cartoons on DVD, under the "Cartoon Network Hall of Fame" name.[71]

The complete series, with the exception of the Ego Trip TV movie and the unaired "Rude Removal" segment, became available on iTunes in 2010.[72] All the seasons of Dexter's Laboratory have been released on Hulu.[73] The video game Cartoon Network Racing contains the episodes "Dexter's Rival" and "Mandarker" (PS2 version only) as unlockable extras.

| Title | Episodes | Release date | Features | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 4 | |||

| "Dexter's Super Computer Giveaway" DVD set | 52 | 1999 | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | The grand prize of a Subway promotion, this DVD includes every episode of the series as of 1999.[74] |

| Volume 1 | 12 | Template:N/a | March 27, 2000[75] | Template:N/a | VHS includes the episodes "Dee Deemensional", "Maternal Combat", "Dexter Dodgeball", "Dexter's Assistant", "Dexter's Rival", "Old Man Dexter", "Double Trouble", "Changes", "Jurassic Pooch", "Dimwit Dexter", "Dee Dee's Room", "Big Sister", "Star Spangled Sidekicks", and "Game Over." |

| Ego Trip | 1 | November 7, 2000[76] | July 23, 2001[77] | Template:N/a | VHS includes the made-for-TV special "Ego Trip" along with "The Justice Friends: Krunk's Date" and "Dial M for Monkey: Rasslor". |

| Greatest Adventures | 8 | July 3, 2001[78] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | VHS includes Genndy Tartakovsky's eight favorite episodes: "Changes", "Dexter's Rival", "Old Man Dexter", "Dexter Dodgeball", "Picture Day", "Quiet Riot", "Last But Not Beast", and "Dexter's Lab: A Story"; as well as a preview of Samurai Jack and a bonus Ed, Edd n Eddy episode: "Stop, Look and Ed".[79] |

| Season 1 | 13 (episodes 1-13) | October 12, 2010[71] | Template:N/a | February 13, 2008[69] | The two-disc DVD includes all episodes from season one with the exception of "Dial M for Monkey: Barbequor", which is replaced by "Dexter's Lab: A Story" on the Region 1 release. The Region 4 release includes all episodes. |

| Season 2 (Part 1) | 19 (episodes 14-32) | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | June 11, 2008[70] | The two-disc DVD includes the first half of episodes from season two. |

| Title | Episodes | Release date | Features | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 4 | |||

| The Powerpuff Girls: Twisted Sister | 1 | April 3, 2001[80] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | "Dexter's Lab: A Story" |

| The Powerpuff Girls Movie | 1 | November 5, 2002[81][82] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | "Chicken Scratch" |

| Powerpuff Girls: 'Twas the Fight Before Christmas |

1 | October 7, 2003[83][84] | Template:N/a | November 8, 2005[85] | "Dexter vs. Santa's Claws" |

| Scooby-Doo and the Toon Tour of Mysteries | 3 | June 2004[86] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | "Trick or Treehouse", "Unfortunate Cookie", and "Photo Finish" |

| Cartoon Network Halloween: 9 Cartoon Capers |

1 | August 10, 2004[87] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | "Picture Day" |

| Cartoon Network Christmas: Yuletide Follies |

1 | October 5, 2004[88] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | "Snowdown" |

| Toon Foolery—Laugh Your 'Ed Off! | 1 | Template:N/a | Template:Unknown | Template:N/a | "Opposites Attract" |

| Toon Foolery—Fool About Laughing! | 1 | Template:N/a | Template:Unknown | Template:N/a | "Blonde Leading the Blonde" |

| Cartoon Network Halloween 2: Grossest Halloween Ever |

1 | August 9, 2005[89] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | "Dee Dee's Room" |

| Cartoon Network Christmas 2: Christmas Rocks |

1 | October 4, 2005[90] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | "Dexter vs. Santa's Claws" |

| Cartoon Network: Christmas Rocks | 1 | Template:N/a | October 18, 2010[91] | Template:N/a | "Dexter vs. Santa's Claws/Pain in the Mouth/Dexter and Computress Get Mandark!" |

| 4 Kid Favorites: The Hall of Fame Collection | 8 (episodes 1-8) | March 13, 2012[92] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | 4-disc compilation set includes Dexter's Laboratory: Season One, Disc One |

| 4 Kid Favorites: The Hall of Fame Collection Vol. 3 | 8 (episodes 1-8) | June 23, 2015[93] | Template:N/a | Template:N/a | 4-disc compilation set includes Dexter's Laboratory: Season One, Disc One (contrary to the packaging stating Disc Two is included instead) |

Music releases

The series has spawned two music albums, Dexter's Laboratory: The Musical Time Machine and Dexter's Laboratory: The Hip-Hop Experiment, three hip hop music videos, and a fourth music video by the band They Might Be Giants for their song "Dee Dee and Dexter", which features Japanese-style animation, as its animation was produced by Klasky Csupo, the studio that made Rugrats.[94] Three Dexter's Laboratory tracks were also featured on the Cartoon Network compilation album Cartoon Medley.[95]

Toys and promotions

In November 1997, Wendy's promoted Dexter's Laboratory with six collectible toys called "Dexter's Lab Creation", "Dexter's Green Test Tube Straw", "Dexter's Grabber", "Dexter's Purple Spark Maker", "Dexter's Pen Stand", and "Dexter's Yellow Noisemaker" in their kids' meals.[96] A Subway promotion lasted from August 23 to October 3, 1999, and included "Dexter's Super Computer Giveaway", in which a computer, monitor, games, software, and an exclusive set of Dexter's Laboratory DVDs were given out to the winner.[74][97] Discovery Zone sponsored Cartoon Network's eight-week-long "Dexter's Duplication Summer" in 1998 to promote the show's new schedule.[98] Toy company Trendmasters released a series of Dexter's Lab figures and playsets in 2001.[99][100] A set of six kids' meal toys was available as part of an April 2001 Dairy Queen promotion.[101] That same month, Cartoon Network and Perfetti Van Melle launched the "Out of Control" promotion, which included on-air marketing and a sweepstakes to win an "Air Dextron" entertainment center.[102] The following April, a similar promotion featured Dexter's Laboratory-themed AirHeads packs and an online sweepstakes.[103] Subway promoted the series a second time from April 1 to May 15, 2002, with four kids' meal toys.[103] In September 2003, Burger King sponsored Dexter's Laboratory toys with kids' meals as part of a larger promotion featuring online games, Cartoon Orbit codes, and new episodes of the series.[104]

Race to the Brainergizer and The Incredible Invention Versus Dee Dee, two board games based on the series, were released by Pressman Toy Corporation in 2001.[105]

Video games

Six video games based on the series have been released: Dexter's Laboratory: Robot Rampage for the Nintendo Game Boy Color,[106] Dexter's Laboratory: Chess Challenge for the Nintendo Game Boy Advance,[107] Dexter's Laboratory: Deesaster Strikes!, also for the Game Boy Advance,[108] Dexter's Laboratory: Mandark's Lab? for the Sony PlayStation,[109] Dexter's Laboratory: Science Ain't Fair for PC,[110] and Dexter's Laboratory: Security Alert! for mobile phones.[111]

A Dexter's Laboratory combat-style action video game for the PlayStation 2 and Nintendo GameCube was set to be developed by n-Space, published by BAM! Entertainment, and distributed by Acclaim Entertainment for a 2004 release, but the project was cancelled.[112][113] On February 15, 2005, Midway Games announced plans to develop and produce a new Dexter's Laboratory video game for multiple consoles, but the game never saw the light of day.[114]

Dexter, Mandark, Dee Dee, Dexter's computer, and Major Glory, along with many items, areas, and inventions from the show were featured in the MMORPG FusionFall.[115][116] Various characters from the series were also featured in Cartoon Network Racing[117] and Cartoon Network: Punch Time Explosion.[118] Punch Time Explosion featured different voice talent for Dexter (Tara Strong instead of Christine Cavanaugh or Candi Milo) and Monkey (Fred Tatasciore instead of Frank Welker).

Books

Fourteen books set in Dexter's Laboratory were released by Scholastic, and a few more by Golden Books. These books were:

Under "Dexter's Laboratory":

- Dexter's Ink (2002) by Howie Dewin (ISBN 0-439-38579-2)

- Dex-Terminator (2002) by Bobbi J. G. Weiss and David Cody Weiss (ISBN 0-439-38580-6)

- Dr. Dee Dee & Dexter Hyde (2002) by Meg Belviso and Pam Pollack (ISBN 0-439-43422-X)

- I Dream of Dexter (2003) by Meg Belviso and Pam Pollack (ISBN 0-439-43423-8)

- The Incredible Shrinking Dexter (2003) by Pam Pollack and Meg Belviso (ISBN 0-439-43424-6)

- Dexter's Big Switch (2003) by Meg Belviso and Pamela Pollack (ISBN 0-439-44947-2)

- Horse of a Different Dexter (2002) by David Cody Weiss and Bobbi J. G. Weiss (ISBN 0-439-38581-4)

- Knights Of The Periodic Table (2003) by David Cody Weiss and Bobbi J. G. Weiss (ISBN 0-439-43425-4)

- Cootie Wars (2003) by David Cody Weiss and Bobbi J. G. Weiss (ISBN 0-439-44932-4)

- Brain Power (2003) by David Cody Weiss and Bobbi J. G. Weiss (ISBN 0-439-44942-1)

- Zappo Change-O (2001, by Golden Books) by Genndy Tartakovsky (ISBN 0-307-99812-6)

The last five of these were unnumbered, at least on the covers.

Under "Dexter's Laboratory Science Log":

- Dee Dee's Amazing Bones (2002) by Anne Capeci (ISBN 0-439-44175-7)

- Mixed-Up Magnetism (2002) by Anne Capeci (ISBN 0-439-38582-2)

- What's the "Matter" with Dee Dee? (2003) by Anne Capeci (ISBN 0-439-47240-7)

- Little Lab or Horrors (2003) by Anne Capeci (ISBN 0-439-47242-3)

Publication details, and book covers for most, are available at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

Additional related books, which are not "story" books are:

- Dexter's Laboratory: Science Fair Showdown! (2001, Golden Books) by Chip Lovitt, a collection of science fair projects. (ISBN 0-307-10775-2)

- Dexter's Joke Book For Geniuses, (2004, Scholastic) by Howie Dewin (ISBN 0-439-54582-X )

See also

Template:Wikipedia books

- List of fictional scientists and engineers

Template:Portal bar

References

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite episode

- ↑ Template:Cite episode

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Template:Cite news

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Simmensky 2011, p. 283.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ http://techjives.net/onvoxshow/?p=190

- ↑ Simmensky 2011, p. 287.

- ↑ Simmensky 2011, pp. 286–287.

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ http://www.tvschedulearchive.com/cartoon-network/2005/072505.txt

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite magazine

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

Bibliography

- Template:Cite book

External links

Template:Commons category Template:Wikiquote

- Template:Official website

- Template:Official website

- Dexter's Laboratory at Cartoon Network's Department of Cartoons (archive)

- Template:IMDb title

- Template:Tv.com show

- Template:Bcdb

- Dexter's Laboratory at Don Markstein's Toonopedia